Modelling customer churn - Part 2

The first of this series of posts introduced the concept of customer churn as time-to-event process, and carried out some preliminary data exploration, and survival analysis for the Telco customer dataset from IBM.

In this second post I’m going to move on to fitting some classification models to the dataset to see how well we can predict which customers are at risk of churning based on the information we have about them.

Assuming you’re continuing from last time, you should have a cleaned data frame with 20 covariates in addition to the class variable “Churn”:

head(df.tel[,1:11], n=3)

customerID gender SeniorCitizen Partner Dependents tenure PhoneService MultipleLines InternetService OnlineSecurity OnlineBackup

1 7590-VHVEG Female 0 Yes No 1 No No service DSL No Yes

2 5575-GNVDE Male 0 No No 34 Yes No DSL Yes No

3 3668-QPYBK Male 0 No No 2 Yes No DSL Yes Yes

head(df.tel[,12:21], n=3)

DeviceProtection TechSupport StreamingTV StreamingMovies Contract PaperlessBilling PaymentMethod MonthlyCharges TotalCharges Churn

1 No No No No Month Yes Electronic\ncheck 29.85 1 No

2 Yes No No No One year No Mailed\ncheck 56.95 34 No

3 No No No No Month Yes Mailed\ncheck 53.85 2 Yes

Last time, we saw that the first covariate is an ID number which we can discard. We also saw that “TotalCharges” was just a proxy for tenure, so that too can be discarded.

df.tel=df.tel[,c(2:19, 21)]

We also saw that contract had the largest effect on churn rate, and that the curves were discontinuous over the contract expiry time. Therefore, it may be helpful to include contract expiry as an additional predictor. (Note that when fitting a predictive model you should ideally split your data then carry out feature engineering using only the training set).

df.tel$contract_expired=F

df.tel$contract_expired[which(df.tel$Contract=="Month" & df.tel$tenure>=1)]=T

df.tel$contract_expired[which(df.tel$Contract=="One year" & df.tel$tenure>=12)]=T

df.tel$contract_expired[which(df.tel$Contract=="Two year" & df.tel$tenure>=24)]=T

We should also check for class imbalance, since it is likely that the numbers churned and not churned are unequal:

table(df.tel$Churn)/nrow(df.tel)

No Yes

0.7346301 0.2653699

We see 27% of customers churned, so there is some class imbalance, but it is not extreme.(You can read more about techniques to correct class imbalance here). For imbalances at a rate of around 0.1 or lower we would need to consider techniques to address the imbalance when fitting models. For now, we’ll use the data as it is.

Next we load the caret library and split our data into training and test sets:

library(caret)

seed = 7

set.seed(seed)

train_index=createDataPartition(df.tel$Churn, p=0.8, list=F)

train_data=df.tel[train_index,c(1:18,20,19)]

test_data=df.tel[-train_index,c(2:18,20,19)]

Caret offers a huge range of models to choose from, many with sophisticated regularisation features. Here, I’ll compare three models: 1) Naive Bayes (simple model we started to explore via plots last time), 2) GLMnet, a linear method: logistic regression with lasso or elastic net regularisation, and 3) Random forest, a non-linear method with regularisation via tree depth.

Note that we mainly have categorical predictors, which Caret will automatically convert to dummy variables (a single binary variable for each category value) during fitting.

I prefer to use the area under the ROC curve as the performance metric so I set this up ready for fitting, also specifying repeated cross validation with 10 folds and repeated 3 times in order to fit the reglularization parameters.

control = trainControl(method="repeatedcv", number=10, repeats=3,

summaryFunction=twoClassSummary, classProbs=TRUE)

metric = "ROC"

preProcess=c("center", "scale")

Fit the three methods to the training set. Note the random forest model is slow due to the cross-validation, so if you have problems reduce the number of repeats or use a smaller training set.

# GLMNET - logistic regression with regularisation

set.seed(seed)

fit.glmnet <- train(Churn~., data=train_data, method="glmnet", metric=metric, preProc=preProc, trControl=control)

# Naive Bayes

set.seed(seed)

fit.nb <- train(Churn~., data=train_data, method="nb", metric=metric, preProc=preProc, trControl=control)

# Random Forest

set.seed(seed)

fit.rf <- train(Churn~., data=train_data, method="rf", metric=metric, preProc=preProc, trControl=control)

Compare performance on the test set using ROC area under the curve. To get full predictive power from the classifier it’s important to get the probability from the predictions, and not just use the raw results which will predict a binary response based on probabilities above or below 0.5. The pROC library also gives an estimate of the 95% confidence interval on the ROC using bootrap resampling.

library(pROC)

compare=data.frame()

rocs=list()

i=1

for (name in c("glmnet", "nb", "rf"))

{

fit = get(paste0("fit.",name))

predictions=predict(fit, test_data, type="prob")

roc.obj=roc(test_data$Churn=="Yes", predictions$Yes)

aucval=auc(roc.obj)[1]

compare=rbind(compare, data.frame(model=name, auc=auc(roc.obj)[1],

auc.lci95=ci.auc(roc.obj)[1],

auc.uci95=ci.auc(roc.obj)[3]))

rocs[[i]]=roc.obj

i=i+1

}

print(compare, digits=3)

model auc auc.lci95 auc.uci95

1 glmnet 0.836 0.813 0.858

2 nb 0.810 0.784 0.835

3 rf 0.814 0.789 0.840

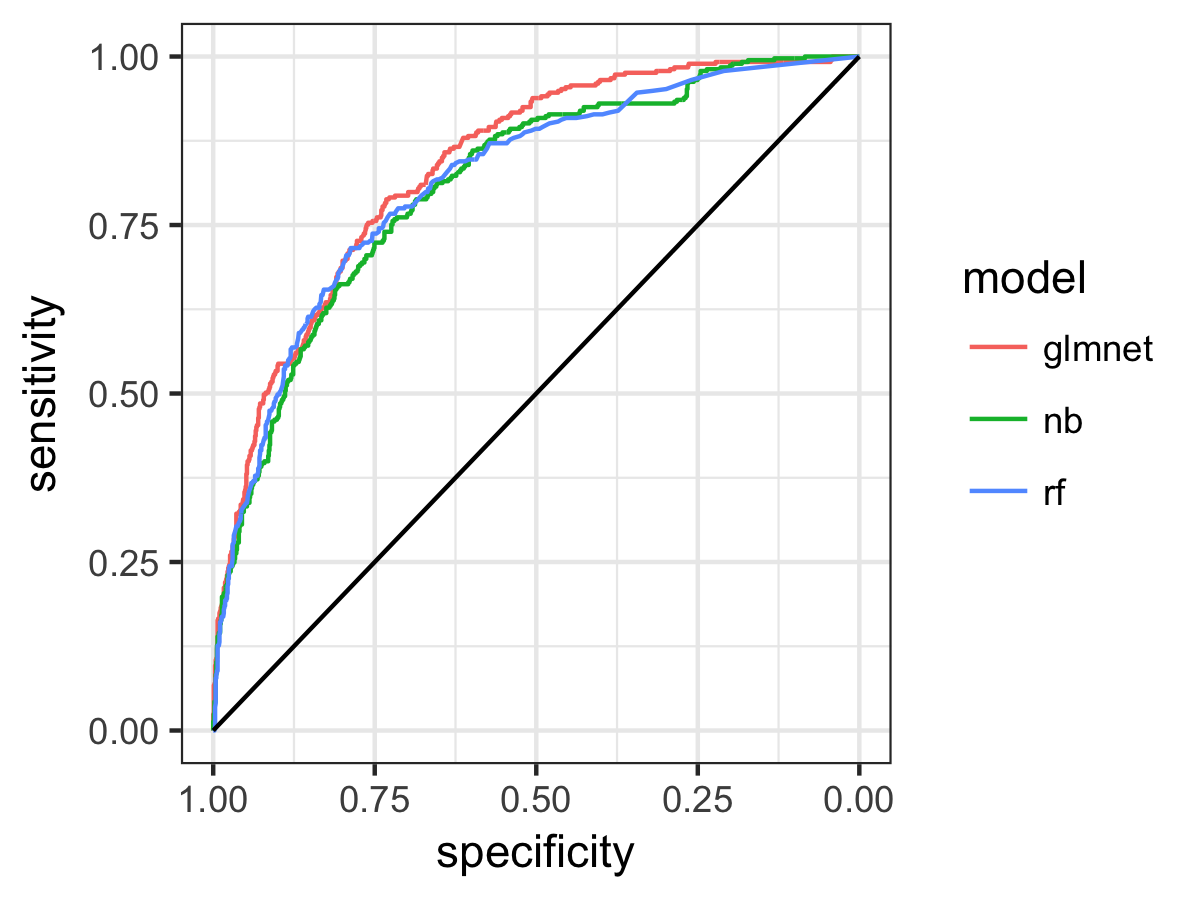

Using the pROC library, we can also plot the ROC curve for the three models, which shows 1-specificity, or the false positive rate (x), plotting against the sensitivity or hit rate (y). The black line shows the performance expected if the forecast consisted of the same probability for all customers, which would give a ROC area of 0.5. A perfect forecast would have a false positive rate of zero (specificity of 1) and a sensitivity of 1: all the data points would be clustered at (1,1) on the plot, giving a ROC area of 1. Therefore the greater the area between the black line and the ROC curve for each model, the more skilful the prediction from that particular model.

ggroc(rocs)+scale_color_discrete("model", labels=modelnames)+theme_bw()+

geom_segment(data=data.frame(x=1, y=0, xend=0, yend=1),

aes(x=x, y=y, xend=xend, yend=yend), color='black')

So the regularised logistic regression model GLMnet comes out top, and performs better than the simplest (unregularised) Naive Bayes method but also better than the Random Forest model. We also see from the overlap of the confidence intervals and the ROC plot that there is not so much difference between the models, but glmnet does look a little better. The ROC area tells us the probability that, two randomly selected customers, one from each category, the probability that the classification model will assign the greater probability of churn to the one that did in fact churn. So, for our best model this ability to distingiush churned customers is around 0.84, and this is significantly better than a non-informative forecast (AUC of 0.5) at 95% confidence.

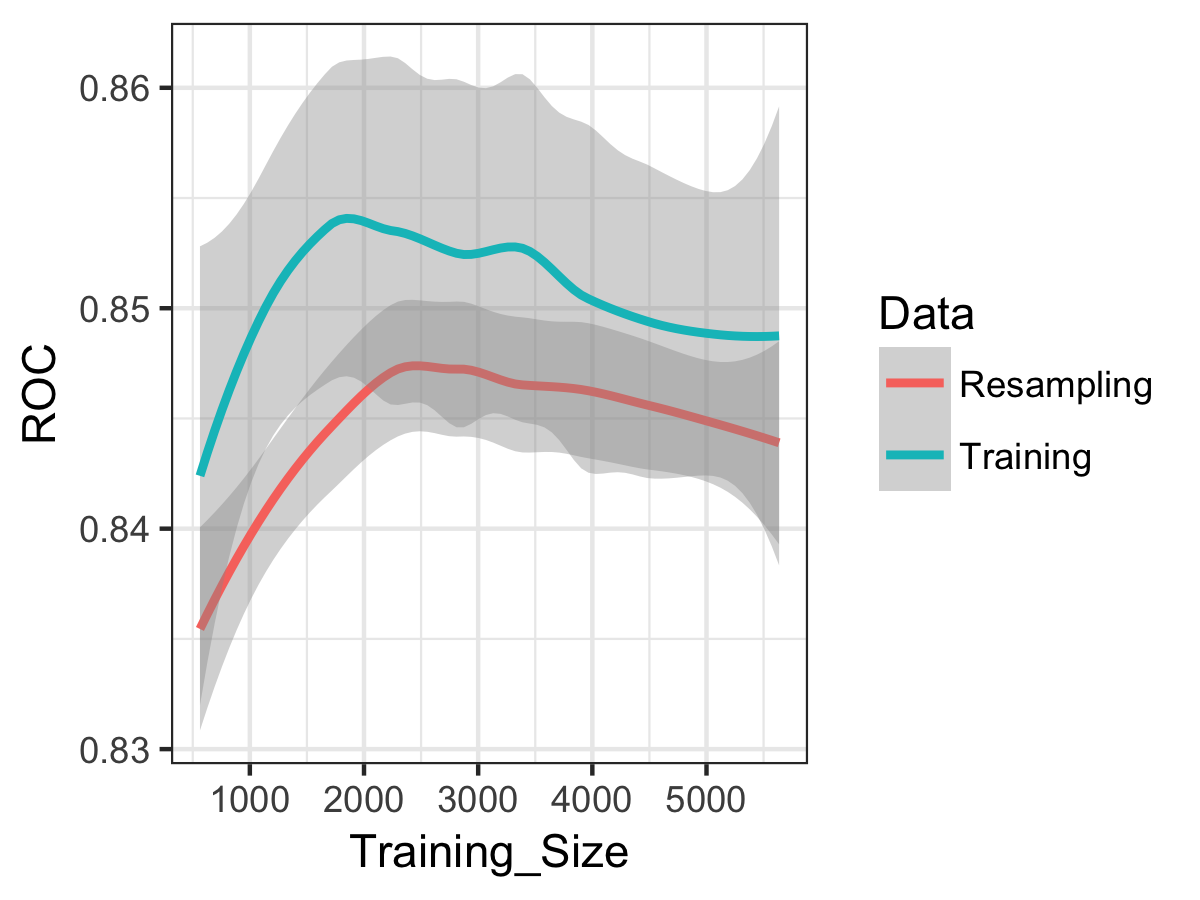

We can use the caret function “learing_curve_data” to plot the learning curve for the models, to tell us if we’d expect a better fit with more data. Let’s do this for the GLMnet model:

# Get dummy predictor vars first

dmy = dummyVars(" ~ .", data = train_data[,1:(ncol(train_data)-1)])

dmy.df = data.frame(predict(dmy, newdata = train_data))

dmy.df=cbind(dmy.df, data.frame(Churn=factor(train_data$Churn)))

lcd=learing_curve_dat(dat=dmy.df,

outcome="Churn",method="glmnet",

metric=metric, trControl=trainControl(

classProbs=T, summaryFunction = twoClassSummary))

ggplot(lcd, aes(x = Training_Size, y = ROC, color = Data)) +

geom_smooth(method = loess, span = .8) +

theme_bw()

We see that error in the model is increasing (i.e. ROC decreases), and the training and resampling errors are changing roughly in parallel. So the model is suffering from bias rather than variance, and more data (from the same distribution) would not likely produce a better-performing and generalisable model. For more on learning, curves, I’d recommend the useful notes here.

Finally, let’s examine the best model fit a little more. For the glmnet model, the coefficients show us the direction of the effect on the churn probability: positive coefficients mean an increased probability of churn and negative coefficients a decreased probability of churn. We can also extract the variable importance from the model fit and rank the predictors.

coeff=predict(fit.glmnet$finalModel, type = "coefficients",

s=fit.glmnet$bestTune$lambda)

coeff

(Intercept) -1.599677889

genderMale .

SeniorCitizen1 0.048102160

PartnerYes -0.007105372

DependentsYes -0.078127959

tenure -0.813825921

PhoneServiceYes -0.067878763

MultipleLinesNo service 0.049543026

MultipleLinesYes 0.126742101

InternetServiceFiber optic 0.474371645

InternetServiceNo -0.043437030

OnlineSecurityNo service -0.043160968

OnlineSecurityYes -0.133554832

OnlineBackupNo service -0.043969565

OnlineBackupYes -0.029928087

DeviceProtectionNo service -0.046420652

DeviceProtectionYes .

TechSupportNo service -0.046329617

TechSupportYes -0.150521863

StreamingTVNo service -0.046892263

StreamingTVYes 0.101179746

StreamingMoviesNo service -0.042586260

StreamingMoviesYes 0.119301524

ContractOne year -0.253784260

ContractTwo year -0.516323995

PaperlessBillingYes 0.137929191

PaymentMethodCredit\ncard -0.012673556

PaymentMethodElectronic\ncheck 0.172840007

PaymentMethodMailed\ncheck .

MonthlyCharges .

contract_expiredTRUE 0.139496261

varImp(fit.glmnet)

glmnet variable importance

only 20 most important variables shown (out of 30)

Overall

tenure 100.000

ContractTwo year 63.444

InternetServiceFiber optic 58.289

ContractOne year 31.184

PaymentMethodElectronic\ncheck 21.238

TechSupportYes 18.496

contract_expiredTRUE 17.141

PaperlessBillingYes 16.948

OnlineSecurityYes 16.411

MultipleLinesYes 15.574

StreamingMoviesYes 14.659

StreamingTVYes 12.433

DependentsYes 9.600

PhoneServiceYes 8.341

MultipleLinesNo service 6.088

SeniorCitizen1 5.911

StreamingTVNo service 5.762

DeviceProtectionNo service 5.704

TechSupportNo service 5.693

OnlineBackupNo service 5.403

So 30 variables were retained in the model, with the five most important being tenure (decrease probability of churning), contract of two years (decrease probability of churning), fiber optic internet (increase probability of churning) contract of one year (decrease probability of churning) and payment method of electronic check (increase probability of churning).

At this point, you might want to check these results against the IBM analysis using Watson Analytics. They find “Contract, Internet Service, Tenure, and Total Charges are the most important factors,” exactly as we have found, although they don’t appear to have spotted that Total Charges and Tenure are exactly the same thing, which just shows you should always plot your raw data!

This classification analysis has moved us beyond simply identifying risk factors to quantifying the predictive power of the covariate information held on customers in terms of indentifying those at risk of churning. However, with this simple approach we are predicting who is at risk of churning for the time snapshot of the dataset. In reality, if we are to take action based on model predictions, we need a prediction of churn risk which is a function of both invariant customer characteristics, and time. This is a more challenging problem which I’ll return to discuss in the third and final post in this series.

Leave a Comment